"THE STORIES WE LEAVE BEHIND ARE THE STORIES THAT CREATE THE FUTURE."

Film Review: Pariah

In most coming-of-age stories the protagonist suffers through the travails of indecision, and of trial and error before finally stumbling upon self-discovery.

The same can’t be said about Alike, our heroine in the critically acclaimed film ‘Pariah’. You see Alike knows just who she is. It’s the people around her who don’t understand her—or themselves, for that matter.

What I expected to be a straight-ahead story of a young black lesbian coming to terms with her sexuality turned out to be something other than that. The story is of an adjusted young black lesbian trying to make sense of a world that doesn’t make sense. From the painful last part of the opening scene where Alike, coming from a night out with her friends, must change from her ‘boyish’ look to the ‘girlish’ look that’s expected of her we’re immediately drawn into her dilemma: how does Alike find the strength to shake off the mask that’s been assigned to her and live her life as it was meant to be?

But there’s more to the story. In ‘Pariah’, we’re not only allowed to see Alike’s pain, but the pain of those around her as they struggle to find ‘a good place to be’ in life, and it’s their own self-appointed failure in life that inflames their outrage against Alike and her kind. Alike and the community of lesbians become the scapegoats.

Pariah is a film whose story offers many thematic layers and complex characters, and the film skillfully handles those elements. The film is shot mostly with close framing giving the audience a feel of the smallness and the angst of the world around Alike, and during moments of warmth and humor (yes, there are moments of humor in this film) the close framing allows the viewer to focus on the beauty of Alike’s world; the pacing of the film is moderate, giving us time to absorb what the characters are experiencing, something that's needed, given the complexity of the characters' situations.

Then there is the acting. The actors gave their all in ‘Pariah’. I wouldn’t take anything away from any of the actors because everyone seemed to have understood the story as a whole, as being about more than just Alike, but about the suffering of the people around her as well. Adepero Oduye who portrays Alike brings a soft strength to the role, strong willed, but not without being understanding; Charles Parnell who plays her father, lets us see someone who knows he must find balance when life deals him an unexpected hand (oh, and he’s hot too, even one of my lesbian friends agreed). I really liked all the actors, from Sahra Mellesse who played Alike’s younger sister; Pernell Walker who plays her best friend Laura; Aasha Davis who plays the little hottie, Bina who steals Alike’s attention, to Shamika Cotton (a native of my hometown Cincinnati), who plays Laura's understanding sister who takes Laura in once the rest of their family disowns Laura.

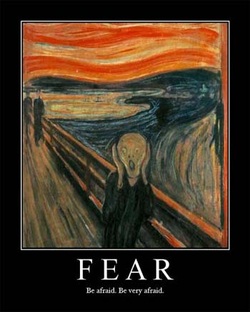

But let’s talk about that Kim Wayans—Damn that woman can act! In the role of Alike’s mother, Audrey, Kim Wayans let us see the fear her character harbors, a fear that she just might not be able to pull off having the perfect family she had dreamed. Audrey is a woman who has placed great demands on her family to the point of alienating them-- and others as well because even at work her co-workers avoid her. She confuses her own self-interest with love of family. It’s a complicated role that could be misconstrued by a less skilled actress as someone who is just angry without truly understanding that it is fear that drives the character. Kim Wayans seemed to have gotten it-- a great performance. Throughout the film I couldn’t take my eyes off Kim Wayans’s eyes and the ongoing dialogue in them.

An added attraction for me was to see further inside a community I’ve only seen glimpses of: the urban hip-hop culture of young, mostly black and brown lesbians. It’s a community that is rarely shown on the big screen, if ever; and no they don’t sit around strumming acoustic instruments like their counterparts we so often see onscreen (btw, I even found out what an ‘AG’ is). The film also addresses some important issues of young LGBT youth like homelessness and disenfranchisement. Oh, and the soundtrack is slamming!

However, Pariah wouldn’t have been this wonderful film without an accomplished director and we have found that in Dee Rees. From a beautifully shot film and the ability to help her actors really understand the complexities of the story, Dee Rees, has proven she has the chops.

The same can’t be said about Alike, our heroine in the critically acclaimed film ‘Pariah’. You see Alike knows just who she is. It’s the people around her who don’t understand her—or themselves, for that matter.

What I expected to be a straight-ahead story of a young black lesbian coming to terms with her sexuality turned out to be something other than that. The story is of an adjusted young black lesbian trying to make sense of a world that doesn’t make sense. From the painful last part of the opening scene where Alike, coming from a night out with her friends, must change from her ‘boyish’ look to the ‘girlish’ look that’s expected of her we’re immediately drawn into her dilemma: how does Alike find the strength to shake off the mask that’s been assigned to her and live her life as it was meant to be?

But there’s more to the story. In ‘Pariah’, we’re not only allowed to see Alike’s pain, but the pain of those around her as they struggle to find ‘a good place to be’ in life, and it’s their own self-appointed failure in life that inflames their outrage against Alike and her kind. Alike and the community of lesbians become the scapegoats.

Pariah is a film whose story offers many thematic layers and complex characters, and the film skillfully handles those elements. The film is shot mostly with close framing giving the audience a feel of the smallness and the angst of the world around Alike, and during moments of warmth and humor (yes, there are moments of humor in this film) the close framing allows the viewer to focus on the beauty of Alike’s world; the pacing of the film is moderate, giving us time to absorb what the characters are experiencing, something that's needed, given the complexity of the characters' situations.

Then there is the acting. The actors gave their all in ‘Pariah’. I wouldn’t take anything away from any of the actors because everyone seemed to have understood the story as a whole, as being about more than just Alike, but about the suffering of the people around her as well. Adepero Oduye who portrays Alike brings a soft strength to the role, strong willed, but not without being understanding; Charles Parnell who plays her father, lets us see someone who knows he must find balance when life deals him an unexpected hand (oh, and he’s hot too, even one of my lesbian friends agreed). I really liked all the actors, from Sahra Mellesse who played Alike’s younger sister; Pernell Walker who plays her best friend Laura; Aasha Davis who plays the little hottie, Bina who steals Alike’s attention, to Shamika Cotton (a native of my hometown Cincinnati), who plays Laura's understanding sister who takes Laura in once the rest of their family disowns Laura.

But let’s talk about that Kim Wayans—Damn that woman can act! In the role of Alike’s mother, Audrey, Kim Wayans let us see the fear her character harbors, a fear that she just might not be able to pull off having the perfect family she had dreamed. Audrey is a woman who has placed great demands on her family to the point of alienating them-- and others as well because even at work her co-workers avoid her. She confuses her own self-interest with love of family. It’s a complicated role that could be misconstrued by a less skilled actress as someone who is just angry without truly understanding that it is fear that drives the character. Kim Wayans seemed to have gotten it-- a great performance. Throughout the film I couldn’t take my eyes off Kim Wayans’s eyes and the ongoing dialogue in them.

An added attraction for me was to see further inside a community I’ve only seen glimpses of: the urban hip-hop culture of young, mostly black and brown lesbians. It’s a community that is rarely shown on the big screen, if ever; and no they don’t sit around strumming acoustic instruments like their counterparts we so often see onscreen (btw, I even found out what an ‘AG’ is). The film also addresses some important issues of young LGBT youth like homelessness and disenfranchisement. Oh, and the soundtrack is slamming!

However, Pariah wouldn’t have been this wonderful film without an accomplished director and we have found that in Dee Rees. From a beautifully shot film and the ability to help her actors really understand the complexities of the story, Dee Rees, has proven she has the chops.

Dr. Martin Luther King: Graven Image, Forgotten Legacy (An Essay From February 2009)

In a time when many black Americans have co-opted Dr. Martin Luther King as the hero of Black America, and during this, the forty-first year since his death, it’s important that we look not only at Martin Luther King, the man, but also at the breadth and the depth of his vision.

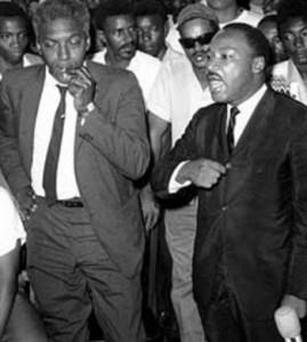

At the time of Dr. King’s death his opposition to hatred and injustice had become more inclusive than just civil rights for black Americans. He spoke out against economic oppression regardless of race; he was outspoken against the war in Viet Nam and he was bold enough to venture into the gay community by turning to an openly gay black man, Bayard Rustin, as a mentor (pictured here with Dr. King). In fact, while Dr. King may have delivered his famous ‘I Have A Dream’ speech during The March on Washington, it was Bayard Rustin who put the march together. Mr. Rustin was the ‘architect of The March on Washington.

These facts about Martin Luther King often go unspoken in the black American community, but if we took time to look at the road Dr. King traveled we wouldn’t be in awe of his liberal, humanitarian ways.

His journey began years before he entered the struggle for civil rights. During his formative years as an intellectual he studied the words not only of Jesus the Christ and Frederick Douglass, but of Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi and Rheinhold Niebuhr as well because he understood that in order to battle inhumanity he must first understand the depth of humanity. This is something so many of us have failed to realize about the vision of Martin Luther King.

I know it was something I hadn’t understood during the time Dr. King was on this earth.

I can remember, as a young black gay man, two days before my fourteenth birthday, standing in front of the T.V. in our living room watching the newsflash of his assassination. Reflecting on that evening, I see a young man who understood enough of the struggle of being black in America, but I also see a young man who felt no one would ever understand the struggle he was going through of being gay in America. I now see I was wrong.

I was wrong because the vision Martin Luther King laid before us did include me as a gay man. It included all peoples who are victims of hatred and injustice.

The person who knew Martin Luther King best, his wife, Coretta Scott King, spent the final years of her life embracing gay rights and speaking openly that her husband, if he had lived on into his later years, would have embraced gay rights. She knew of Martin’s dream and she carried it to the end of her days.

Dr. King’s vision was dynamic in that it transcended the darkness of hatred and ignorance and embraced the light of love. Now I understand that on the evening Dr. King took his last breath, I, a young black gay man, did inhale the sweetness of his dream and is why I continue to savor his words and the words of his wife who continued his dream:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”~ Dr. Martin Luther King

"We are all tied together in a single garment of destiny . . . I can never be what I ought to be until you are allowed to be what you ought to be," ~ Dr. Martin Luther King

“Like Martin, I don’t believe you can stand for freedom for one group of people and deny it to others.” ~ Coretta Scott King

"Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood," ~ Coretta Scott King

(2009, by Doug Cooper Spencer)

At the time of Dr. King’s death his opposition to hatred and injustice had become more inclusive than just civil rights for black Americans. He spoke out against economic oppression regardless of race; he was outspoken against the war in Viet Nam and he was bold enough to venture into the gay community by turning to an openly gay black man, Bayard Rustin, as a mentor (pictured here with Dr. King). In fact, while Dr. King may have delivered his famous ‘I Have A Dream’ speech during The March on Washington, it was Bayard Rustin who put the march together. Mr. Rustin was the ‘architect of The March on Washington.

These facts about Martin Luther King often go unspoken in the black American community, but if we took time to look at the road Dr. King traveled we wouldn’t be in awe of his liberal, humanitarian ways.

His journey began years before he entered the struggle for civil rights. During his formative years as an intellectual he studied the words not only of Jesus the Christ and Frederick Douglass, but of Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi and Rheinhold Niebuhr as well because he understood that in order to battle inhumanity he must first understand the depth of humanity. This is something so many of us have failed to realize about the vision of Martin Luther King.

I know it was something I hadn’t understood during the time Dr. King was on this earth.

I can remember, as a young black gay man, two days before my fourteenth birthday, standing in front of the T.V. in our living room watching the newsflash of his assassination. Reflecting on that evening, I see a young man who understood enough of the struggle of being black in America, but I also see a young man who felt no one would ever understand the struggle he was going through of being gay in America. I now see I was wrong.

I was wrong because the vision Martin Luther King laid before us did include me as a gay man. It included all peoples who are victims of hatred and injustice.

The person who knew Martin Luther King best, his wife, Coretta Scott King, spent the final years of her life embracing gay rights and speaking openly that her husband, if he had lived on into his later years, would have embraced gay rights. She knew of Martin’s dream and she carried it to the end of her days.

Dr. King’s vision was dynamic in that it transcended the darkness of hatred and ignorance and embraced the light of love. Now I understand that on the evening Dr. King took his last breath, I, a young black gay man, did inhale the sweetness of his dream and is why I continue to savor his words and the words of his wife who continued his dream:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”~ Dr. Martin Luther King

"We are all tied together in a single garment of destiny . . . I can never be what I ought to be until you are allowed to be what you ought to be," ~ Dr. Martin Luther King

“Like Martin, I don’t believe you can stand for freedom for one group of people and deny it to others.” ~ Coretta Scott King

"Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood," ~ Coretta Scott King

(2009, by Doug Cooper Spencer)

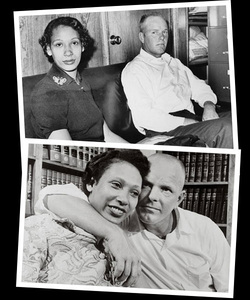

Audio & Text Transcript: 1966 Loving v Virginia (Argument Over Interracial Marriage Before the Supreme Court)

As we near the Supreme Court’s decision on same-sex marriage, I thought I would re-visit the Supreme Court’s decision on interracial marriage from the 1966 ‘Loving v Virginia’ case. I have an actual AUDIO RECORDING of the proceedings as well as TEXT transcript here.

It’s interesting to hear and read the proceedings from just 47 years ago, hearing similar thought that’s now being applied today for and against same-sex marriage. And to think that it has been only 47 years ago that the nation was before, in discord over the right to marry. What's of particular interest are the views of granting marriage and of states' rights when granting marriage, right of inheritance as well as defining race and class. (I made notation in bold and underlined text of passages that caught particular attention as I read through the transcript.)

Audio(go to site and scroll down to audio link): http://www.oyez.org/cases/1960-1969/1966/1966_395

Text Transcript:

Argument of Philip J. Hirschkop

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Number 395, Richard Perry Loving, et al., Appellants, versus Virginia.

Mr. Hirschkop.

Mr. Cohen: Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court.

I'm Bernard S. Cohen.

I would like to move the admission of Mr. Philip J. Hirschkop pro hac vice, my co-counsel in this matter.

He's a member of the Bar of Virginia.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Your motion is granted.

Mr. Hirschkop, you may proceed.

Mr. Hirschkop: Thank you Your Honor.

Mr. Chief Justice, Associate Justices, may it please the Court.

We will divide the argument.

Accordingly, I will handle the Equal Protection argument as we view it and Mr. Cohen will argue the Due Process argument.

You have before you today what we consider the most odious of the segregation laws and the slavery laws and our view of this law, we hope to clearly show is that this is a slavery law.

We referred to the law itself -- oh at first, I'd like to bring the Court's attention, there are some discrepancy in the briefs between us and the common law especially as to which laws are in essence.

They have particularly said that Section 20-58 and 20-59 of the Virginia Code are the only things for consideration by this Court, and those two Sections, of course, are the criminal section, making a criminal penalty for Negro and white to intermarry in the State of Virginia.

20-58 is the evasion section under which this case particularly arose which makes it a criminal act to people who go outside the State to avoid the laws of Virginia to get married.

We contend, however, Your Honors that there is much more in essence here.

That there's actually one simple issue, and the issue is, may a State proscribe a marriage between two adult consenting individuals because of their race and this would take in much more in the Virginia statutes.

Sections 20-54 and 20-57 void such marriages and if they void such marriages, you would only decide on 20-58 and 20-59, these people, whether they go back to Virginia and they are in Virginia now, will be subject to immediate arrest under the fornest -- fornication statute, and the lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute and more than that, there are many, many other problems with this.

Their children would be declared bastards under many Virginia decisions.

They themselves would lose their rights for insurance, social security and numerous other things to which they're entitled.

So we strongly urge the Court considering this to consider this basic question, may the state proscribe a marriage between such individuals because of their race and their race alone.

Justice John M. Harlan: How many states (Inaudible)?

Mr. Hirschkop: There are 16 states, Your Honors that have these States.

Presently, Maryland just repealed theirs.

These all are southern states with four or five border southern states as Oklahoma and Missouri, and Delaware.

There have been in recent years two Oklahoma and Missouri that have had bills to repeal them but they did not pass the statute.

Now, in dealing with the equal protection argument, we feel that on its face, on its face, these laws violate the equal protection of the laws.

They violate the Fourteenth Amendment, and in dealing this, we look at the arguments advanced by the State and there're basically two arguments advanced by the State.

On one hand, they say the Fourteenth Amendment specifically exempted marriage from its limitations.

On the other hand, they say if it didn't, the Maynard versus Hill doctrine would apply here, that this is only for the State to legislate them.

In replying to that, we think their health and welfare aspect of it is in essence and we hope to show to the Court, these are not health and welfare laws.

These are slavery laws pure and simple.

Now for this reason, we went to some length in our brief to go into the history of these laws, to look at why Virginia passed these laws and why other States have these laws on a books and how they used these laws.

Without reiterating what is in the brief, I will just refer to that history very briefly.

As we pointed out in the brief, laws go back to the 1600s.

The 1691 Act is the first basic Act we have.

There was a 1662 Act which held that the child of a Negro woman and a white man would be free or slave according to the condition of his mother.

It's a slavery law and it was only concerned with one thing, and it's an important element in this matter.

Negro man, white woman, that's all they were really concerned with.

I think maybe all these still concern with.

It's purely the white woman, not purely the Negro woman.

These laws robbed the Negro race of their dignity.

It's the worst part of these laws and that's what they're meant to do, to hold the Negro class in a lower position, lower social position, the lower economic position.

1691 was the first basic Act and it was entitled an Act for this pressing of outline slaves and the language of the Act is important while we go back to it because they talk about the prevention of bad abominable mixture and spurious issue and we'll see that language time and again throughout all the judicial decisions referred to by the State.

And then they went into two centuries of trying to figure out who these people were that they were proscribing.

I won't touch upon all the States.

I understand amicus will do that.

But at one time, in 1705 it was a person with one-eight or more Negro blood and then in 1785, it became person with one quarter or more and it went on and on.

It wasn't until 1930 that we finally arrived that what a Negro is in the State of Virginia, that's a person with any traceable Negro blood, a matter which we think defies any scientific interpretation.

And the first real judicial decision we get in Virginia was in 1878 when the Kinney versus Commonwealth case came down.

And there again, we have a very interesting decision because in Kinney versus Commonwealth, they talk about the public policy of the State of Virginia.

Now what that public policy was and how would it be applied?

If Your Honors will indulge me, I have the language here which is the language that had carried through, through the history of Virginia.

And they talk about spurious issue again, and that is what's constantly carried through and carried through for an act to suppressing of outlawing slaves.

And they talk about the church southern civilization, but they didn't speak about the southern civilization as a whole but this white southern civilization.

And they want the race as kept distinct and separate, the same thing this Court has heard since Brown and before Brown, but it's heard so many times during the Brown argument and since the Brown argument.

And they talk about alliances so unnatural that God has forbidden them and this language --

Justice Hugo L. Black: Would you mind telling me what case that was?

Mr. Hirschkop: That's Kinney versus Commonwealth, Your Honor.

Justice Hugo L. Black: Kinn --

Mr. Hirschkop: Kinney, K-I-N-N-E-Y and then in 1924, in the period of great history in the United States, the historical period we're all familiar with, a period when the west was in arms over the yellow peril and western states were thinking about these laws or some (Inaudible), a period when the immigration laws were being passed to the United States because the north was worried about the great influx of Italian immigrants and Irish immigrants, a period when the Klan rode openly in the south and that's when they talked about bastardy of races, and miscegenation and amalgamation and race suicide became the watch word, and John Powell, a man we singled out in our brief, a noted pianist of his day, started taking up the Darwin Theory and perverting it through the theory of eugenics, the theory that applied to animals, to pigs, and hogs, and cattle.

They started applying it to human beings.

In taking Darwinism that the Negro race was a stepping stone, was that lost men we've always been looking for between the white man and the abominable snowman whoever else, they went back.

And that's when the Anglo-Saxon Club was formed in the State of Virginia and that's when Virginia Legislature passed our present body of law.

They took all these old laws.

These antebellum and postbellum laws and they put them together into what we presently have.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: How many states for the first time in that -- in the 20s passed these kinds of laws, do you recall?

Mr. Hirschkop: Your Honor, to the best of our knowledge, basically most States had them.

It was just Virginia and then Georgia copied the Virginia Act which had such a complete act and it was described in many places as the most perfect model with this type of Act.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: But you were saying that the western states and the eastern states and others during the 1924 period passed these laws as I understood you.

Mr. Hirschkop: Most -- No Your Honor, most of them actually had them on the books.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: I see, alright.

Mr. Hirschkop: They -- with summary codification, this one Virginia strove to do this to make a perfect model law and only Georgia thought it was expected from our reading of history that many other States would follow but they just let remain what they had.

There was very few repeals on those days.

Actually, the great body of repeal has been since Brown with 13 states have repealed since that time.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Yes.

Well, what relevance do that 1924 period have to this?

Mr. Hirschkop: Because some of the statutes we have were enacted then, all the registration statutes were enacted in 1924 Your Honor.

These are the statutes basically which you have to have a -- a certificate of racial composition in the State of Virginia.

The statutes which we find absolutely mostly odious, the statutes will reflect back the Nazi Germany and to the present South African situation.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: I see.

Mr. Hirschkop: But the present bill, as it is on the books is that law from 1924 and it was entitled "A Bill to Preserve the Integrity of the White Race" when it was initially issued.

It was passed as a bill for racial integrity -- to preserve racial integrity.

Now, we would advance the argument very strongly to the Court, they're not concerned with racial integrity of the Negro race, only with the white race.

In fact in Virginia, it's only a crime for white and Negro to intermarry and the lowest couch in such terms that they say, "White may only marry white" in Section 20-54 of our law, but it goes on from there to make it a crime only for whites and Negroes to intermarry.

There's no crime for Malaysian to marry a Negro and it's a -- it's a valid marriage in Virginia but it would be a void marriage for Malaysian or any other race aside from Negro to marry a white person.

A void marriage but there'd be no criminal penalty against anyone but the white person.

They were not concerned with the racial integrity but racial supremacy of the white race.

In 1930, they finally, as I said before, went on, say any person with traceable Negro blood with a Negro.

Now, these laws, Your Honors, are ludicrous in their inception and equally ludicrous in their application.

It's not possible to look at just the Virginia laws alone.

You have to look at what happened in the whole south we feel and the classifications in the south.

It's impossible to say.

I won't go to again, the exact illustration of Negroes but South Carolina, North Carolina make certain Indians white people.

North Carolina, Cherokee and Robeson County is a white person, all of the Cherokee Indians, and Negroes.

In South Carolina is the Kato Indians and these laws came to invent to these other very hateful laws.

In Mississippi advocate of social equality under the mis -- miscegenation body of law.

It's a criminal penalty.

I think it carries one to five years.

If Your Honor please, there are several decisions handed out by States which again point out the racial feeling concerning these laws.

The Missouri laws bottomed on States versus Jackson which basically held that if the progeny of a mixed marriage, married the progeny of a mixed marriage, there'd be no further progeny and fundamentally ridiculous statement.

Maybe it wasn't for those men in that day and age but it certainly is now and Georgia has an equally ridiculous basis for the laws.

In Scott versus Georgia where they held that from the daily observances, they see that the offspring of such marriages are feminine.

And in this case, and I will refer to the appellant's brief here at page 35, the Loving case comes to you based on the case of Name versus Name.

Now, what were they talking about in Name versus Name?

Again, they wanted to preserve the racial integrity of their citizens.

They want not to have a mongrel breed of citizens.

We find there no requirement that the State shall not legislate to prevent the obliteration of racial pride but must permit the corruption of blood even though it weakens or destroy the quality of the citizenship.

These are racial and equal protection thoroughly proscribes these.

In the case before you, the opinion of the lower court, Judge Bazile, and we have the footnote in page 37 of our brief, which says, "Almighty God created the right races, white, black, yellow, malay, and red and he placed them on separate continents," and I didn't read the whole quote, but it's a fundamentally ludicrous quote and again, that's what they're talking about.

We feel the very basic wrong of these statutes is they rob the Negro race of their dignity and fundamental in the concept of liberty in the Fourteenth Amendment is the dignity of the individual, because without that, there is no ordered liberty.

We've quoted from numerous authorities and particularly not for the scientific point but particularly, I refer you to the quotes fromGunner Murdel (Gunnar Myrdal) who's made a noted study in recent years of this, and not the old studies that are otherwise quoted.

Your Honor please, there's one other issue that the State raises that I will touch on briefly, and that's the Fourteenth Amendment issue.

To begin with the state advances, no history of the Fourteenth Amendment debates themselves.

They go to the debates of the 1866 Act and the Freedmen's Bureau Bills which did immediately precede the Fourteenth Amendment and then in their own brief, they have an excellent cite that the Fourteenth Amendment was impart designed to provide a firm constitutional basis for the Civil Rights Act.

We would advance that the in part is the answer to the Fourteenth Amendment.

Even if you read in the history, the 1866 Act, it's much broader in scope.

Its language is much broader in the scope.

The language of liberty, due process is much broader than the rights, privileges and immunities that were put in to the 1866 legislative act.

It was more than an effort to put these laws beyond the grasp before the Congress.

It was a greater protection.

And Your Honor please, even if you want to take the history of the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, we feel even reading that language, that wasn't clear.

It's up to the Court to decide what happened.

Many legislators felt it would proscribe, that the Civil Rights Act itself, would proscribe this type of laws in the States.

Even various proponents said amalgamation laws were now touched and basically what they rely on in their brief, and in their argument in the court below, and I might point out to Your Honors that this was argued fully in the court below and the Virginia Supreme Court didn't base the rule on the argument, but push to the side and went to the merits of whether these laws were or were not unconstitutional, taking into account before taking them.

As I recall, this was put before this Court in the McLaughlincase, well I know it was and it was put before the lower court in McLaughlin cases, the same argument.

Now while McLaughlin was cohabitation, I think you'd have to read those laws together if they were intended to be reached because they spoke of amalgamation laws in the arguments of the 1866 Act.

But even if you would read the language of Senator Trumbullwhich they rely on so strongly, what did he really say?

Well, one point page 17 in their brief, he says, "I presume there is no discrimination in this respect" and he goes on to talk about his argument, the law as I understand it in all States applies equally.

This was the Pace reasoning which this Court has set aside, but the real tip off we feel on this comes on page 22 where they're quoting Trumbull again.

And he says, "This bill would not repeal the law to which the senator refers," in reply to Senator Johnson, "if there is no discrimination made by it, if there is no discrimination made by it."

We submit very strongly as it had been before the Court many times that the application of the Fourteenth Amendment is an open-ended application even on these laws, even when we had this argument, because this is if it's not discriminatory, Your Honors must reach the conclusion whether it's discriminatory or not and it is clearly discriminatory.

We speak of this on page 30 and 31 of our brief, quoting Bickel, a noted constitutional authority.

He said, "They were open-ended and meant to be expanded in light of changing times and circumstances" and quoting this Court from Burton versus Wilmington Parking authority, "Its constitutional assurance was reserved in terms of imprecision was necessary if the right were to be enjoyed in the variety of individual State relations."

There are any number of such quotes in your opinions in the last ten years.

The same argument you had before you all the time that the Fourteenth Amendment doesn't apply.

Your Honors very adequately answered that argument in the McLaughlin decision when you said, "This was essential purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment" and we submit very strongly, it is the essential purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment.

If Your Honors please in resting on the equal protection argument, we fail to see how any reasonable man can but conclude that these laws are slavery laws were incepted to keep the slaves in their place, were prolonged to keep the slaves in their place, and in truth, the Virginia law still views the Negro race as a slave race, that these are the most odious laws to come before the Court.

They robbed the Negro race of its dignity and only a decision which will reach the full body of these laws in the State of Virginia will change that.

We ask that the Court consider the full spectrum of these laws and not just the criminality, because it's more than a criminality that's at point here, that the legitimacy of children right to inherent land, the many, many rights, and in reaching a decision, we ask you reach on that basis.

Thank you Your Honors.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Mr. Cohen.

Argument of Bernard S. Cohen

Mr. Cohen: Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court.

We were here merely to obtain a reversal on behalf of Richard Perry Loving and Mildred Jeter Loving.

I think Mr. Hirschkop would have presented a cogent and complete argument based upon the Equal Protection Clause which would leave no course but to find the statutes question unconstitutional.

However, while there is no doubt in our minds that these statutes are unconstitutional and have run afoul of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, we urge with equal strength that the statutes also run afoul of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Now, whether one articulates in terms of the right to befree from racial discrimination as being due process under the Fourteenth Amendment or whether one talks of the right to be free from infringement of basic values implicit in ordered liberty as Justice Harlan has said in the Griswold case, citing Palko versus Connecticut or if we talk about the right to be free from arbitrary and capricious denials of Fourteenth Amendment liberty as Mr. Justice White has said in the concurring opinion in Griswold or if we urge upon this Court to say as it has said before in Myer versus Nebraska and Skinner versus Oklahoma that marriage is a fundamental right or liberty and whether we go further and urge that the Court say that this is a fundamental right of liberty retained by the people within the meaning of the Ninth Amendment and within the meaning of liberty in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Justice Potter Stewart: Well, surely that's -- there's some limit on that.

I suppose you would agree that -- that a State could forbid a marriage between a brother and a sister, wouldn't you?

Mr. Cohen: We have conceded that the State may properly regulate marriages and may regulate divorces and indeed they have done so and this Court has upheld certain regulations.

I don't know whether the issue of consanguinity or affinity has ever been here but certainly the one that comes to my mind first would be the Reynolds case in the polygamy matter and that we have no trouble distinguishing those, and I -- I don't think the Court will either.

There was no race question involved.

Justice Potter Stewart: No, but you're -- you're not arguing about any race question.

You're arguing complete freedom to contract, aren't you, under the Due Process Clause?

Mr. Cohen: Well, I -- I have stated that the Due Process Clausehas been subject to many articulations.

And what I was going to go on to say was that all of these articulations can find some application in this particular case.

If you ask me for the strength of the argument of the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause as applied to this case, I urge most strongly that it be on the basis of the Fourteenth Amendment is Amendment to protect against racial discrimination.

However, I do not think that the other arguments are completely invalid.

I -- I don't even know if the Court ever has to reach them, but one can still argue that there is liberty and a right to marry as this Court has said in Myer and Skinner and that in no way, detracts from our argument that they cannot -- the State cannot infringe upon the right of Richard and Mildred Loving to marry because of race.

These are -- these are just not acceptable grounds.

We are talking about an arbitrary and capricious ground and we -- we should have no trouble.

Justice Potter Stewart: But some -- some people might think it was reasonable that it's arbitrary and capricious to forbid first cousins to marry each other, state rights to live does have such a law prohibiting first cousins for marrying each other.

Now the -- because large body of opinion might think that's arbitrary and capricious.

Does that mean that the State has no constitutional power to pass such a statute?

Mr. Cohen: I believe that we run into another step before we can reach that Your Honor and that is the burden of coming forth with the evidence.

I think that a State can legislate and can restrict marriage and might even be able to go so far as to restrict marriage between first cousins as some States have.

And I think that if that case were before the Court, they would not have the advantage that we have of a presumption being shifted and a burden being shifted to the State to show that they have a reasonable basis for proscribing inter-racial marriages.

However, if we were here on a first cousins case, I think we would have the tougher road to hoe because we would have to come in and show that the proscription was arbitrary and capricious.

It was not based upon some reasonable grounds, and that is a difficult thing for an appellant to do.

Thankfully, we are not here with that burden.

The State is and we submit that the State cannot overcome that burden.

Not only do we submit that they cannot but for the purposes of this case, we certainly submit they have not.

Nowhere in the State's brief, nowhere in the legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment, nowhere in the legislative history of Virginia's antimiscegenation statutes, is there anything clearer than would -- Mr. Hirschkop has already elucidated that these are racial statutes to perpetuate the badges and bonds of slavery.

That is not a permissible state action.

Justice Black: Was there any effort to repeal the law in Virginia?

Mr. Cohen: Your Honor, there have not been any efforts and I can tell you from a personal experience that candidates who run for office for the state legislature have told me that they would, under no circumstances, sacrifice their political lives by attempting to introduce such a bill.

There is one candidate who has indicated that he would probably do so at some time in the future, but most of them have indicated that it would be political suicide in Virginia.

Justice Hugo L. Black: May I ask you if you're arguing the due process question on the theory that even if the Court holds that violates the Equal Protection Clause it is necessary to go on and reach the broad expanses you mentioned?

Mr. Cohen: Your Honor, we should be very pleased to have a decision from this Court that all of the statutes are unconstitutional based upon the Equal Protection Clause.

However, what we are concerned about is that the Court, if it uses the equal protection argument to find the statute unconstitutional that there might be some way that Virginia could possibly get around this by reenacting a statute that was -- that would absolutely, only permit whites to marry whites, Negroes to marry Negroes, Malaysians to marry Malaysians, and possibly might -- we might be back here again.

Justice Hugo L. Black: I don't see how that would be possible if the Court held, according to the first argument, this is a plain violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

Mr. Cohen: Well, I -- I quite agree Your Honor and I -- I do think that the equal protection argument is -- is the strongest argument, that is the correct argument and it is the basis upon which we strongly urge the Court to rule.

We are mostly concerned about a narrow ruling that would not go to the whole section of statutes.

There are 10 sections, Section 20-50 through 20-60 and this is our chief concern that the Court might not touch the racial composition certificate statute.

Justice Hugo L. Black: The what?

Mr. Cohen: The racial composition certificate, Section 20-50 says that anybody in Virginia who applies to the State registrar vital statistics shall be given a certificate of racial composition.

He goes and he says -- he goes up to the clerk of the Court and says, "I'm white.

I want a certificate of racial composition or I'm white or Negro.

I want a certificate of racial composition that I'm Negro."

And if the clerk looks at him and believes him, he him fill out something and certifies that to the way it looks to him this person is white, or is Negro, and he sends down to Richmond and he gets a certificate of racial composition.

To the best of my knowledge, this has not been used in recent years and I don't know what is its extent was.

Back around 1924, except the legislative history shows that they brought in the state registrar of vital statistics and he testified that there was great confusion under the old law as to who is a member of which race and that they were having a little bit of difficulty determining who is a member of which race and who could be proscribed from marrying whom and called for this very strict statute which now says that white persons may only marry white persons.

Therefore, what they've done is make it a crime for a white person to marry a Negro or a Negro person to marry a white person, but it's not a crime for a Negro to marry a Malaysian.

It's a void marriage in Virginia and they may be prosecuted for violation of the fornication statutes but not for violation of the -- of the antimiscegenation statute.

The Section 20-54 merely makes civil disability apparent in a white -- in a marriage between a -- a white and a Malaysian or a Negro and a -- a -- well, we're not exactly sure about that but between a white and anybody else, but another white or a Negro, it is not a criminal act and therefore, they are under great civil disability.

They -- the children are illegitimate.

The white cannot --

Justice Hugo L. Black: Could that -- could that possibly be fit through if the Court should decide to straight out that the State cannot prevent a marriage, the relationship of marriage between the whites and the blacks because of their color.

Mr. Cohen: Absolutely not.

That would be no problem.

Justice Hugo L. Black: That would settle it, wouldn't it?

Mr. Cohen: Yes, I think it would.

Justice Hugo L. Black: That would settle it constitutionally.

Mr. Cohen: I believe it would.

The enormity of the injustices involved under this statute is -- merely serves us indicia of how the civil liabilities amount to a denial of due process to the individuals involved.

As I started to say before, no matter how we articulate this, no matter which theory of the Due Process Clause or which emphasis we attach to, no one can articulate it better thanRichard Loving when he said to me, "Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."

I think this very simple layman has a concept of fundamental fairness and ordered liberty that he can articulate as a brick layer that we hope this Court has set out time and time again in its decisions on the Due Process Clause.

With respect to the legislative history urged by the State as being conclusive that the Fourteenth Amendment did not mean to make unconstitutional State statutes prohibiting miscegenation.

We want to emphasize three important points.

One, only a small group of Senators in any of the debates cited ever expressed themselves at all with respect to the miscegenation statutes.

There are perhaps five or six that are even quoted and these were for the Freedmen's Bureau Bill in the Act -- Civil Rights Act of 1866.

If absence of debate ever has any influence at all, this is a classic case.

Nowhere has the State been able to cite one item of legislative debate on the Fourteenth Amendment itself with respect to antimiscegenation statutes, not one item.

All of their references are to the 1866 Act.

And again, we point out that those comments were very carefully worded by both proponents and opponents of the bill.

Again, we carefully point out that their own record of the legislative history shows that they were just as many Senators who believed that indeed, especially the Southern Senators who States had antimiscegenation statutes, they were just as many of them who did believe that the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 would invalidate such an Act.

Their own passages that they printed in the brief around pages 30 through 33 are replete with support for our argument that -- that the -- at best, at best, the legislative history is inconclusive.

And as this Court has found before and we hope will continue to find, the Fourteenth Amendment is an amendment which grows and can be applied to situations as our knowledge becomes greater and as our progress is made and that there will be no problem in finding that this set of statutes in Virginia are erroneous to the Fourteenth Amendment.

I have been questioned about the right of the State to regulate marriage and I think that where the Court has found that the State could in fact regulate marriage within permissible grounds, they've gone on as they did in the Reynolds case to find that the people that there was a danger to the principles on which the Government of the people to a greater or lesser extent rests.

I ask this Court if the State is urging here that there is some State principle involved or some principle of the people involved that is a proper principle of theirs, what is it?

What is the danger to the State of Virginia of interracial marriage?

What is the state of the danger to the people of interracial marriage?

This question has been carefully avoided.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: What is the order -- have you agreed upon an order or -- or I would think Mr. Marutani would probably be next?

Mr. Cohen: Probably in my understanding Mr. Chief Justice?

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Yes.

Well, that would be the normal way.

Mr. Marutani, you may proceed.

Argument of William M. Marutani

Mr. Marutani: Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court.

My name is William Marutani, legal counsel for the Japanese American Citizens League which has filed a brief amicus curiae in this appeal.

On behalf of the Japanese American Citizens League, I would like to thank this Court for this privilege.

Because the issues before this Court today revolve around the question of race, may I be excused in making a brief personal reference in this regard?

As a Nisei, that is American born and raised in this country but whose parents came from Japan, I am and I say this with some trepidation of being challenged, perhaps among those few in this courtroom along with the few other Nisei who happened to be here this morning, who can declare with some degree of certainty, the verity of his race, that is at the term race is -- as defined as an endogamous or inbreeding geographic population group.

This means the broad definition of convenience utilized by anthropologists.

Now, those who would trace their ancestry to the European cultures where over the centuries, there have been invasions, cross-invasions, population shifts with the inevitable cross-breeding which follows and particularly those same Europeans who have been part of the melting pot of America, I suggest would have a most difficult, if not impossible task of establishing what Virginia's antimiscegenation statutes require namely, and I quote, proving that, "No trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian."

This is what Virginia statutes would require.

Incidentally, this presupposes that the term Caucasian is susceptible of some meaningful definition.

A burden incidentally which Virginia's laws somehow conveniently overlooks, but then this same infirmity applies to the remaining 15 States which have similar antimiscegenation laws.

Now, one of the most sophisticated anthropologists with all their specialized training and expertise, flatly reject the notion of any pure race and in this connection.

I refer to the UNESCO proposal, a statement on race which is attached to Appendix A to the amicus brief, and incidentally, also signed by Professor Carleton Coon who is a very frequently cited by those who would uphold racial differences.

Now, notwithstanding the fact that anthropologists, reject, flatly reject the concept that any notion of a pure race under Section 20-53 of Virginia's laws, that clerk or the deputy clerk is endowed with the power to determine whether an applicant for a marriage license is, "Of pure white race," a clerk or his deputy.

Moreover, the common law of Virginia would have layman as its clerks, judges and juries, take a vague and scandalous terms such as colored person, white person, Caucasian and apply them to specific situations coupled with the power in this layman to invoke civil and criminal sanctions where in their view an interpretation of these terms, the laws of Virginia had been violated.

I believe no citation is required to state or to conclude that this is vagueness in its grossest sense.

I refer the Court again to the decision of this Court in Giaccio versus Pennsylvania decided in 1966 in which the Court stated,"Such a law which leaves judges and jurors free to decide without any legally fixed standards what is prohibited and what is not in each particular case fails to meet the requirements of the Due Process Clause.

Now, let us assume arguendo that race -- there are such things as definable races within the human species that these can be defined with sufficient clarity and certainty as to be accurately applied in particular situations and further let's assume that the State of Virginia's laws do exactly this and incidentally, all of this is something that the anthropologist have not been able to do it, we submit but nevertheless, the antimiscegenation laws of Virginia and its sister states are unconstitutional.

For if the antimiscegenation laws purport to preserve morphologic or physical differences.

That is a differences essentially in the shape of the eyes, the size of noses or the texture of hair, pigmentation of skin, such differences are meaningless and neutral.

They serve no proper legislative purpose.

To state the proposition in itself is to expose the other absurdity.

Moreover, the antimiscegenation laws would take the aspiration of marriage which is common to all people and which is otherwise blessed by the State and which institution incidentally has found of course upon one of man's biological grimes, it would take this and solely on the base of rates, it would convert it into a crime.

In McLaughlin where this Court considered a Florida statute which involved " concepts of sexual decency dealing with extramarital and premarital promiscuity, this Court nevertheless struck down such statute because it was formulated on racial classification and thus laid an unequal hand on those who committed intrinsically the same quality of offense.

Now, for the appellants here, Richard Loving and Miller Loving marriage in and of itself is not a crime.

It is not an offense even under Virginia Clause.

By Virginia Clause, it was their race, it was their race which made it an offense.

Incidentally while Mr. Loving apparently admitted that he was white and thereby admitted to the fact which rendered his marriage a criminal act under Virginia's laws, it is suggested that he was incapable of making a knowing admission that he was "A pure white race" or "Had no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian."

Now, we further submit that the antimiscegenation laws involved an unequal application of the laws.

Virginia's express state policy for its antimiscegenation laws has been declared to maintain "Purity of public morals, preservation of racial integrity as well as racial pride and to prevent a mongrel breed of citizens."

However, under these antimiscegenation laws since only white persons are prevented from marrying outside of their race and all other races are free to intermarry and within this particular context, they're free thereby to despoil one another and destroy their racial integrity, purity and pride, Virginia's laws are exposed for exactly what they are, a concept based upon racial superior -- superiority that of the white race and white race only.

Now, we submit that striking down of the antimiscegenation laws, well first of all, not to do certain things.

It will not force anyone to do what he presently does not wish to do.

It does not force anyone to marry outside of his race by striking down the antimiscegenation laws.

By striking down the antimiscegenation laws, no one is called to do, undo anything what she has already done and in this connection, perhaps a distinction maybe made to the Brown case or the School Desegregation cases.

On the contrary by striking down the antimiscegenation laws, freedom of choice will be restored to all individuals including those who are opposed to racial intermarriage.

For the white person who marries another white person does not, under Virginia's laws as they now stand has any other choice.

We submit that race as a factor has no proper place in state's laws that governing whom a person by mutual choice may or may not marry.

Now, the major such statutory intervention upon personal freedom may be exposed by applying the same operative racial principle in reverse.

Let us suppose that the State of Virginia exercised its powers of determining -- of applying this racial principle so that it decreed at every citizen must marry a person of a different race, this would indeed be shocking that the same operative principle is happen to be geared in a way it is presently geared makes it no less shocking and the meaning to the citizen.

A question was raised --

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Well, wouldn't you -- wouldn't you concede Mr. Marutani that if the law provided that the other races so-called must not intermarry that the law would be good?

Mr. Marutani: No, sir.

Mr. Chief Justice, we submit that first of all, it is no answer to a compound what we believe to be wrong.

Moreover, as a practical matter, who is to determine -- who is to categorize how many races there?

The anthropologists range from two to 200, live in South and they are the so-called, experts.

They are unable to agree.

If anthropologist cannot agree, I would assume that it would be extremely difficult for the legislators to determine and then having determined it to apply it.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Yes.

The reason I ask it was because there were some and had mentioned what you have said that -- that they were denied equal protection in that there was not the same prohibition against intermarrying of the so-called races.

Mr. Marutani: The -- I believe the thrust of that argument sir is that to expose this law for exactly what it is.

It is a White Supremacy Law.

Justice Hugo L. Black: May I ask you, it's not material perhaps in any way, but do you happen to know whether there are laws in Japan which prohibits the other marriage between Japanese and what you might call a Caucasian or white people?

Mr. Marutani: Well, Mr. Justice Black, I might answer that I do not know except by custom.

I can state for example that my own mother would have strenuously objected to my marrying a person of the white race.

Now, Mr. Justice Potter I believe raised the question as towhether or not the State properly has a function to play in the area of control of marriage.

Reference is made to consanguinity, and of course to other standards, mentality, age.

Justice Potter Stewart: Age and I -- I suppose number of spouses.

Mr. Marutani: Yes.

Now, we submit that the racial classification cannot be equated with these standards because racial classification is not an additional standard which is added on the same level as these standards was -- were just enumerated.

They are superimposed over and above all these other standards.

To restate it in another way, the standards of consanguinity, mentality, age and number of spouse and so forth apply to all races, white, black, yellow, it doesn't matter to all races without any distinction, but now the racial factor is superimposed over and above this and is therefore is not on the same level.

It is something different.

It is something additional and over and above on a different level.

Thank you.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Mr. McIlwaine.

Argument of R. D. Mcilwaine Iii

Mr. McIlwaine: Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court.

As an Assistant Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Virginia, I appear as one of counsel for the appellee in support of the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of our State affirming the constitutional validity of the two statutes which are involved in this case.

In view of what has been said before, it may not be inappropriate at this point to emphasize that there are only two statutes before this Court for consideration, Section 20-58 and 20-59 of the Virginia code.

These statutes in their combined effect, prohibit white people from marrying colored people and colored people from marrying white people under the same penal section and forbids citizens of Virginia of either race from leaving the State with intent and purpose of evading this law.

No other statutes are involved in this case.

No attempt has been made by any Virginia officials to apply any other statute to the marital relationship before this Court.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia can be read from beginning to end without finding any other statute mentioned in it except 20-58 and 20-59 with the exception of that one provision which relates to the power of Court to suspend the execution of sentence upon which ground the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia referred this case back to the lower court to have a new condition of suspension imposed.

With that exception, only two provisions of the Virginia Code are mentioned.

Therefore, we take the position that these are the only statutes before the Court and anything that may have to do with any other provision of the Virginia Code which imposes a prohibition on the white race only or has to do with certificates of racial composition, whatever they may be, are not properly before this Court.

This is a statute which applies to a Virginia situation and forbids the intermarriage of the white and colored races.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: It falls on the question of equal protection, maybe your -- your section which allows anyone with one-sixteenth or less of Indian blood to -- to intermarry with the -- with whites would have some significance, would it not where -- where that this one says, anyone who has got a colored blood in them cannot marry with the white.

Mr. McIlwaine: That would only be significant Mr. Chief Justice with respect to that provision 20-54 which is not before the Court which says that a white person shall not marry any other save a white person or a person having no other admixture of blood and white and American-Indian.

That is a special statute.

That is the 20-54 statute against which I myself could find a number of constitutional objections perhaps in that it imposes a restriction upon one race alone which it does not oppose on the other races and therefore, more stringently curtails the rights of one racial group.

But so --

Chief Justice Earl Warren: But you do put a restrictions on North American-Indians if they have more than one-sixteenth of Indian blood in them, do you not?

Mr. McIlwaine: Yes, sir.

But this is because in Virginia, we have only two races of people which are within the territorial boundaries of the State of Virginia in sufficient numbers to constitute a classification with which the legislature must deal.

That is why I say the white and the colored prohibition here completely controls the racial picture with which Virginia is faced.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: You have no Indians in Virginia?

Mr. McIlwaine: Well, we have Indians Your Honor, but this is the point that we make with respect to them.

Under the census figures of 1960, 79 and some odds hundreds percent of the Virginia population was made up of white people, 20 and some odd hundred percent of the Virginia population was made up of colored people, whites and Negroes by definition of the United States Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census.

Thus, 99 and 44 one hundredths percent of the Virginia population falls into these two racial categories.

All other racial classes in Virginia combined do not constitute as much as one-fourth of 1% of the Virginia population.

Therefore, we say that this problem of the intermarriage of whites and orientals or Negroes and orientals or any of these two classes with Polynesians or Indians or Asiatic Indians is not a problem with which Virginia has faced and one which is not required to adopt its policy forbidding interracial marriage too.

A statute of course does not have to apply with mathematical precision, but on the basis of the Virginia population, we respectfully submit that the statute before the Court in this case does apply almost with mathematical precision since it covers all the dangers which Virginia has a right to apprehend from interracial marriage in that it prohibits the intermarriage of those two groups which constitute more than 99% of the Virginia population.

Now, so far as the particular appellants in this case are concerned, there is no question of constitutional vagueness or doubtful definition.

It is a matter of record, agreed to by all counsel during the course of this litigation and in the brief that one of the appellants here is a white person within the definition of the Virginia law, the other appellant is a colored person within the definition of Virginia law.

Thus, the Court is simply faced with the proposition of whether or not a State may validly forbid the interracial marriage of two groups, the white and the colored in the context of the present statute.

Justice John M. Harlan: Does Virginia have a statute under (Inaudible)?

Mr. McIlwaine: No, sir.

It does not.

We have the question of whether or not that marriage would be recognized as valid in Virginia even though it was contracted by parties who are not residents of the State of Virginia under the conflict of laws principle that a marriage valid were celebrated is valid everywhere.

This would be a serious question and under Virginia law, it is highly questionable that such a marriage would be recognized in Virginia, especially since Virginia has a very strong policy against interracial marriage and the implementing statutes declare that marriages between white and colored people shall be absolutely void without decree of divorce or other legal process, the implementing statute which forbids Virginia citizens to leave the State for the purpose of evading the law and returning, the exception to the conflict of laws principally I've stated that a marriage valid was celebrated would be valid everywhere except where contrary to the long -- to the strong local public policy.

The Virginia statute here involved thus expresses a strong local public policy against the intermarriage of white and colored people.

Now, with respect to any other interracial marriage, this -- the policy of the Virginia statutes here involved does not express any sentiment at all.

And we do not have any decision of the Virginia Supreme Court Mr. Justice Harlan which would shed light on that proposition insofar as other races are concerned.

Justice John M. Harlan: (Inaudible)

Mr. McIlwaine: Well, the -- it has been suggested that it would.

I do not know whether Virginia is -- or any State --

Justice John M. Harlan: That is beside the point?

Mr. McIlwaine: Yes, sir.

Is requires to recognize a marriage which is contrary to its own law, especially with respect to matters within its own State.

Now, the appellants of course have asserted that the Virginia statute here under attack is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment.

We assert that it is not, and we do so on a basis of to contentions and two contentions only.

The first contention is that the Fourteenth Amendment viewed in the light of its legislative history, has no effect, whatever upon the power of States to enact antimiscegenation laws specifically, antimiscegenation laws forbidding the intermarriage of white and colored persons and therefore as a matter of law, this Court under the Fourteenth Amendment is not authorized to infringe the power of the State.

That the Fourteenth Amendment does not read in the life of its history, touch much less diminished the power of a States in this regard.

The second contention, an alternative contention is, that if the Fourteenth Amendment be deemed to apply to State antimiscegenation statutes, then these statutes serve a legitimate, legislative objective of preventing a sociological, psychological evils which attend interracial marriages, and is a -- an expression, a rational expression of a policy which Virginia has a right to adopt.

So far as the legislative history of the amendment is concerned, we do not understand that this Court has ever avowed in principle, the proposition, that it is necessary in construing the Fourteenth Amendment to give effect to the intention of the Framers.

With respect to the instant situation, you are not presented with any question involving a dubious application of certain principles to a situation which was unforeseen or unknown to those who framed the principles.

The precise question before this Court today, the validity under the Fourteenth Amendment of a statute forbidding the marriage of whites and Negroes was precisely before the Congress of the United States 100 years ago when it adopted the amendment.

The situation is perfectly clear that those who considered the amendment against a charge of infringing state power to forbid white and colored marriages, specifically excluding that power from the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Do you get that from the debates on the Fourteenth Amendment?

Mr. McIlwaine: Yes Your Honor.

We get it from the -- specifically from the debates --

Chief Justice Earl Warren: Where did you -- where did you quote that in your brief?

Mr. McIlwaine: We get it specifically Your Honor, from the debates leading to the Fourteenth Amendment, the debates on the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 --

Chief Justice Earl Warren: That is a little different though, isn't it?

Mr. McIlwaine: Only to this extent, Your Honor.

The Fourteenth Amendment has been construed by members of this Court a number of times in its historical setting.

The Court has said on a number of instances that the specific debates on the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 which act ultimately became the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment are the most material relating to the Fourteenth Amendment.

Now in this situation, by the time the Freedmen's Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 had been debated and passed, the issue of whether or not the Fourteenth -- the Civil Rights Act of 1866 would infringe the power of the States to pass antimiscegenation statutes was so completely settled, that when the Fourteenth Amendment resolution was brought on, the question was no longer considered to be in open one.

The dissent on our brief and pointed out by the adversaries that we take the position that the Fourteenth Amendment was designed in part to place the Civil Rights Act of 1866 in the Constitution beyond the reach of shifting congressional majority.

We say in part only because as Mr. Justice Black has pointed out in his dissent in the Adamson case, there were a number of reasons why people thought the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment was included.

Some people thought that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was absolutely unconstitutional and that it was necessary to pass an amendment to validate it.

Others thought that the Act was perfectly constitutional but that it could be repealed and that it was necessary to place it in the Constitution to keep it from being repealed.

Still, others thought that the First Section of the Fourteenth Amendment was nothing but the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 in another shape.

Nobody suggested that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and its adoption into the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution expanded the rights which were covered in the 1866 Bill.

And certainly no one suggested that what was expressly removed from the 1866 Act was reinserted in the Constitution in the Fourteenth Amendment within a period of just a few months.

Now, the debates on the Civil Rights Act of 1866 clearly show that the proponents, those who had the billion charge, those who were instrumental in passing the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment clearly in answer to questions put by their adversaries stated in no uncertain terms that the Bill had no application to the States' powerto forbid marriages between white and colored persons, not simply amalgamation but specifically between white and colored persons.

This was repeatedly stated by Senator Trumbull who was the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who steered the bill to the passage and was instrumental in passing the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment by Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, who was the leading Republican member on the Joint Committee of Reconstruction of Fifteen, and by various other members who supported the Bill, and steered it to passage.

Now, text writers have disagreed as to whether or not the charge that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 would invalidate state laws was seriously made or whether it was made for political purposes simply as a smoke screen.

Regardless of the purpose for which it was made, the historical fact remains that the challenge was put by those who disagreed with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, that it would affect the power of the States to pass antimiscegenation statutes, and the proponents and the managers who had the bill in charge absolutely denied that it would have any such effect.

No one who voted for sponsored or espoused the Civil Rights Act of 1866 dared to suggest that it would have the effect of invalidating state antimiscegenation statutes.

Plus, we have a clear intent on the part of those who framed and adopted the amendment to exclude this area of state power from the reach of the amendment.

And this history is buttressed by the fact that the state legislatures, which ratified the amendment, clearly did not understand that it would have any effect at all upon their power to pass antimiscegenation statutes.

Justice Abe Fortas: Mr. McIlwaine, what do you with this Court's decision in the McLaughlin against Florida?

I don't believe you discussed that in your brief, at least I don't remember that you did.

Mr. McIlwaine: No sir, we do not.

We simply say that it relates to a statute which is above and beyond or extraneous to the interracial marriage statutes specifically left this question open for future decision and the question left open in McLaughlin is now here.

Justice Abe Fortas: I -- I understand that but your adversaries can -- made deal of comfort in McLaughlin in theory and principle and with respect to the specific points you are making here.

Mr. McIlwaine: I do not think they take any comfort from McLaughlin with respect to the legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment, Your Honor.

They take comfort of course from the dicta of Mr. Justice Stewart that it is impossible for a State under the Fourteenth Amendment to make the criminal act turn upon the color of the skin of the individual and if that dicta for stands unchallenged, they have reason to take out -- proponent in this case --

Justice John M. Harlan: (Inaudible)

Mr. McIlwaine: But it has nothing [Laughter] to do with the Fourth -- the legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment nor do I understand it in McLaughlin that the Court considered this point.

Justice John M. Harlan: (Inaudible) narrower simply because the statute in that case is the statute in this case (Inaudible)

Mr. McIlwaine: Yes sir but we could -- we do not put forward the proposition but the Pace case does justify the statute.

Justice John M. Harlan: Well, I understand.

Mr. McIlwaine: I mean, so if they want to take comfort in that, that's --

Justice John M. Harlan: They can be --

Mr. McIlwaine: -- let them be our guests.

We simply say that the power of the State to forbid interracial marriages, if we get beyond the Fourteenth Amendment, can be justified on other grounds.

Justice John M. Harlan: Your basic -- your basic position (Inaudible) the jurisdiction of this Court, given what you say is the -- the legislative history of (Voice Overlap) that is your basic --

Mr. McIlwaine: That is our basic position.

Yes, Your Honor.

Justice Fortas: But McLaughlin could not have been decided, perhaps McLaughlin could not have been decided as it was if the court had accepted that premise.

Mr. McIlwaine: The legislative history?

Justice Fortas: Yes.

Mr. McIlwaine: Well, I don't know that the legislative history would support the proposition with respect to the statute of lewd and lascivious cohabitation and so forth.

My legislative history or the legislative history which we are set out specifically relates to interracial marriage.

Justice John M. Harlan: The legislative history, it was raised (Inaudible)

Mr. McIlwaine: Well, so far as this case is concerned, we would like to point out one fact which -- or one circumstance which we think is analogous.

Perhaps, the most far reaching decision of this Court, so far as the popular mind is concerned in the last quarter of the century has been Brown against Board of Education.

In that case, the matter was argued in 1952 and in 1953, this Court restored the case to docket for re-argument and entered an order in which it had called the attention of all counsel in that case to certain matters which the Court en banc wished to have counsel consider.

The first of these questions was, and I'm quoting now from the Court's order, "What evidence is there that the Congress which submitted, and the state legislatures, and conventions which ratified the Fourteenth Amendment contemplated or did not contemplate, understood or did not understand that it would abolish segregation in public schools?"